IP basics in Life sciences

This time, we are going to talk about generic drugs and biosimilars. These days in Japan we don’t hear the word “zoro”, but up until about 20 years ago, generic drugs were commonly referred to as “zoro.” The word “zoro” stems from the Japanese expression “zorozoro” that conjures the image of “creeping in” or moving “one after another” and was used to represent what happens after an original drug patent expires. And in fact, multiple generic drugs are launched for one original drug, but do you know how generic drugs are actually developed and launched into the market? Well, let’s take a look.

But before that, if you haven’t already read the first and second volumes of this column, please do so before continuing as it will make it easier for you to understand what we will be talking about here.

Volume 1: First, let’s talk about medicine classification and patents

Volume 2: Wow! The success rate of drug development is shockingly low!

Vol. 5: Do they really creep in?

– Development schedules of Generics and Biosimilars –

As you may recall, there are two types of unbranded drugs: generic drugs and biosimilars. In this volume, I’ll focus primarily on the research and development of generic drugs, while also briefly touching on biosimilars.

From Development to Market Launch of Generic Drugs

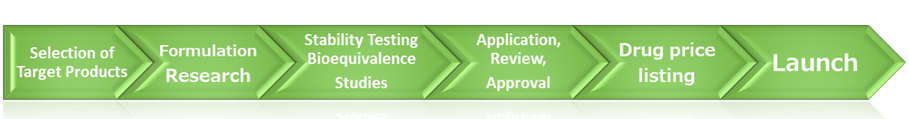

Generic drugs are medicines that are approved after the patent for a brand drug has expired and are recognized as being biologically equivalent to the brand drug in terms of the active ingredients and specifications. The diagram below shows the develop process of generic drugs. Let’s take a closer look, starting at the far left -selection of target products.

Selection of Target Products

This process begins by identifying a target product among the brand drugs that are nearing patent expiration. Since the development period for a generic drug typically spans three to four years, the process is initiated by working backward from the anticipated launch date.

Popular brand drugs with a large market size tend to attract numerous generic competitors, resulting in a flood of generics entering -creeping into- the market immediately after patent expiry. Recently, however, the number of brand drugs based on small molecules has declined, so generics are being developed regardless of market size.

Formulation Research

After selecting the target product, the process moves on to formulation research. Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient in the same quantity as the brand drug, and must match in terms of indications, efficacy, dosage, and administration method. However, as long as the route of administration is the same, the dosage form itself does not need to be identical. Furthermore, the composition other than the active ingredient may differ, provided bioequivalence with the brand drug is maintained. This allows unbranded drug manufacturers to conduct independent formulation research.

Stability Testing and Bioequivalence Studies

Following formulation development, stability testing is conducted to assess or predict the product’s quality during distribution. Since the quality of the active ingredient has already been established by the brand maker, generics are generally approved based on data from accelerated stability tests.

Next comes the bioequivalence study, which confirms that the generic drug is biologically equivalent to the brand drug. This study is critical for regulatory approval, as it ensures therapeutic equivalence, i.e., it will be as effective as the brand drug in treating the patient. If the generic demonstrates comparable bioavailability, i.e., how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream and is available for your body to use after you take it, to the brand drug, it is considered biologically equivalent.

However, for water-soluble intravenous formulations administered directly into the bloodstream (with 100% bioavailability), bioequivalence data is not required if the product is intended solely for intravenous use.

Application, Review, and Approval

After the bioequivalence studies, a Generic Drug Application is submitted to the MHLW. Subsequently the PMDA reviews the application from a pharmacological perspective looking at stability and equivalence, and also confirms that there is no infringement possibility of the brand patents (patent linkage).

Upon successful review, the product is approved by the MHLW and can be launched in the market after price listing on the National Health Insurance drug price list. Generic drug approvals are issued in February and August, with price listings occurring in June and December.

What About Biosimilars?

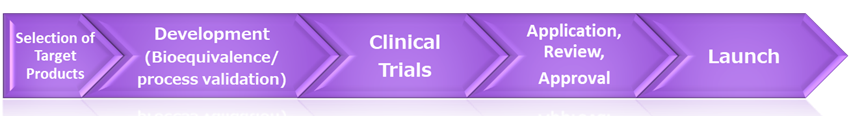

Like generic drugs, biosimilar development begins by selecting a target product. However, the subsequent process differs significantly. A biosimilar is defined as “a pharmaceutical product that is comparable in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy to the reference biologic.” Therefore, biosimilars must be “similar” to the brand biologic in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy—necessitating clinical trials similar to those conducted for brand products.

After regulatory review, the approval process for biosimilars follows the same path as for brand and generic drugs. Once biosimilars are approved they are price listed on the National Health Insurance drug price list in May and November.

The development of a biosimilar typically takes 3 to 5 years, with clinical trials requiring an additional 2 to 5 years. The application and approval process adds another 1 to 2 years, resulting in a total development period of approximately 6 to 12 years. Development costs are estimated at ¥20 to ¥30 billion (roughly USD 130–200 million), making biosimilar development notably more demanding than that of generic drugs.

When Unbranded Drugs Enter the Market…

When generic drugs and biosimilars enter the market, brand companies sometimes file lawsuits claiming patent infringement. You might wonder, “if unbranded drugs only launch after the original patent expires, there should be no infringement issues, right?” Wrong. Brand drugs are often protected by multiple patents—not just one. And patent interpretation isn’t always black and white. Differences in how brand and unbranded manufacturers interpret these patents can lead to disputes, and ultimately, litigation.

Over the past decade, these patent battles have resembled the “Samurai Era.” While I’ll cover some specific patent battles in a future volume, in the next one, I’ll introduce the basics of patent battles—that is, patent litigation. Stay tuned!

Author Profile

Yasuko Tanaka

President & CEO, S-Cube Corporation / Patent Attorney, S-Cube International Patent Firm

Outside Director, Strategic Capital Inc.; Part-time Lecturer, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School; Technical Advisor for IP-related Litigation

Ms. Tanaka graduated from Chiba University (Biochemistry) in 1990. She has worked in the IP Dept. of Teijin, Pfizer Japan and 3M Japan dealing with global patent prosecution both in English and Japanese, IP strategy/consulting, transactions, and IP education. She resigned from her last company, 3M Japan, in March 2013 to start her own venture “S-Cube Corporation” (IP Business Consultancy) in April. In August, she expanded her firm establishing S-Cube International Patent Firm.